Harris’s List

of Covent Garden Ladies

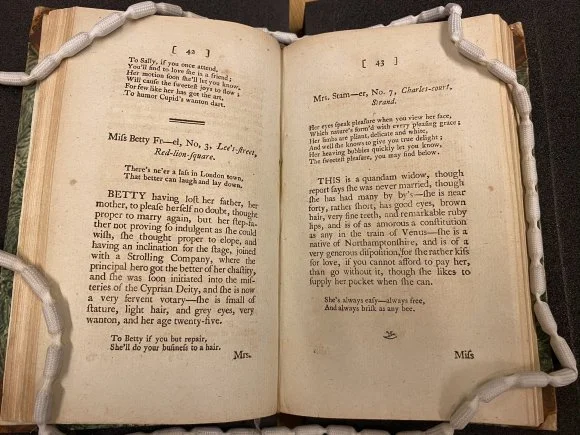

Harris’s List of Covent Garden Ladies was an annual publication of the higher end of Georgian London’s prostitutes and courtesans printed roughly 1757-1795. Produced in a time when, according to Magistrate Saunders Welch’s 1758 estimation, at least one in five women in London were full or part-time sex workers, the List served as a pimp and guide for its wealthier, educated male readership to the best, worst, and middling choice of women in the nation’s capital.

Each entry contains a woman’s name, usually only a surname with the vowels removed for anonymisation, a characterising description, her age, price, address, some specialties or defects, and sometimes an erotic or humorous anecdote. The thousands of women named across the individual entries making up the Lists, each having anywhere from around 90 to over 200 in one volume, are generally rendered through voyeuristic, objectifying, misogynistic language. The stories of their ‘debauching’ or deflowering–usually through rape–are recounted in the same titillating, erotic prose as the stories of their romps with famous clients, who included politicians, wealthy merchants, eminent lawyers, and even royals. Both aspects are intended to serve as an advertisement for the woman’s services, and to induce clients to visit them. Although the works are often violent, uncomfortable, and deeply upsetting, they are nonetheless incredibly valuable historical sources that, although diminishing these women’s agency and humanity, serve as testimony and evidence for the lives of tens of thousands of women otherwise silent in the historical record and generally treated with scorn, contempt, and condescension on account of their profession when they are made visible.

Throughout the List’s publication, especially after the likely original author Samuel Derrick died in 1769, they passed through the hands of multiple anonymous publishers and authors and suffered serious degradations of quality that limits our use of them as reliability historical sources. Particularly towards the late 1780s and 1790s, some entries are repeated but simply paired with a different woman’s name and address. As Nicola Parsons and Amelia Dale noted in 2022, this particularly happened with women who were not white, British, or were otherwise othered in the landscape of Georgian London, marginalising them along racial or ethnic lines and further dehumanising them.

Although this repetition and the increasingly poetic, overly verbose, and classical tone the work adopted as it progressed has led some scholars of eighteenth-century literature and social history to argue the work was primarily intended to be used as erotica for private, personal use and not an actual guidebook, surviving contemporary evidence in satirical illustrations, previous owner’s handwritten notes in the books themselves about particular women, as well as the addresses of known brothels being featured consistently as they arose and moved away from Covent Garden and towards modern-day Soho, Fitzrovia, and Marylebone, where the majority of the Pink Plaque Project’s girls feature, all point to their consistent use for soliciting the service of prostitutes up until the very end.

The Lists ended after nearly forty years when two of its three publishers were prosecuted in a remarkable obscenity trial in 1794 and 1795, the third having just passed away. Already outdated in a changing literary and cultural climate that increasingly saw prostitution and female sexuality as publicly unacceptable, there were no attempts to revive the List despite numerous imitations and counterfeits appearing throughout the 1780s and 90s.

Prostitution, of course, did not disappear with it: an 1800 report by Patrick Colquhoun, a pioneer of modern policing, estimated around 50,000 women worked as prostitutes in London, a city of around one million at the time. The higher-ranking set of these women now worked in high-end brothels or privately out of their own well-furnished residences in fashionable new areas, usually with a few fellow prostitutes whom they lived–a far cry from the rowdy, public heyday of Covent Garden, with girls bursting out of its many bawdy houses, bathhouses, and taverns as depicted in William Hogarth A Rake’s Progress III: The Tavern or The Orgy, the header for this website’s home page.

Moving into the infamously rigid Victorian Era, which viewed prostitution as a death sentence for a fallen woman rather than the natural recourse of inherently libidinous women who performed a necessary evil, London’s female sex workers once again fell back into the shadows and the silence of the historical record, although how much of a voice they were given in the Lists in the first place is still a matter of debate.

Open Access to Harris’s Lists

Here is a hyperlinked list of the few surviving editions of Harris’s List that are accessible to the public:

1761 (on this link, the 1761 edition can be found using the top button, labelled “Zeitschriftenband”)

1766 (on this link, the 1766 edition can be found using the middle button, labelled “Zeitschriftenband”)

1791 (on this link, the 1791 edition can be found using the bottom button, labelled “Zeitschriftenband 1791”)