What is

The Pink Plaque Project?

The Pink Plaque Project is a London-based public history project modelled after English Heritage’s blue plaques, which engage passer-by in the history of where they live, work, and walk and encourage them to think about the cultural and historical landscape of the city by showing them where famous or notable figures had lived.

Pink was chosen as the colour of the plaques due to its modern connotation with women and femininity and its convenient contrast with the masculine blue of English Heritage’s plaques. The colour pink, and the specific shade Rose Pompadour chosen for this project, is also highly relevant to the period the women of this Project belonged to. In the West, pink was ‘invented’ in 1757 (likely the same exact year Harris’s List began publication) by French King Louis XV’s famous mistress Madame de Pompadour. Prior to this point pink was a lighter shade of red, but after de Pompadour began fashioning her gowns, porcelain, and other precious, beautiful objects in her signature stunning shade, created for her by the famed French porcelain maker Sèvres, pink became the most fashionable colour of the later eighteenth century, and European aristocrats of all genders used it as a marker of wealth and status.

It was not until the next century that pink would acquire its familiar soft, feminine connotations–since it was derived from red, a strong, bold colour, in this period men wore pink with pride. Given that many of the women in this Project were or aspired to be the most fashionable, and thus most expensive, women in their trade, this luxurious colour is used for their plaques to signify both their place in society and their strength as individuals.

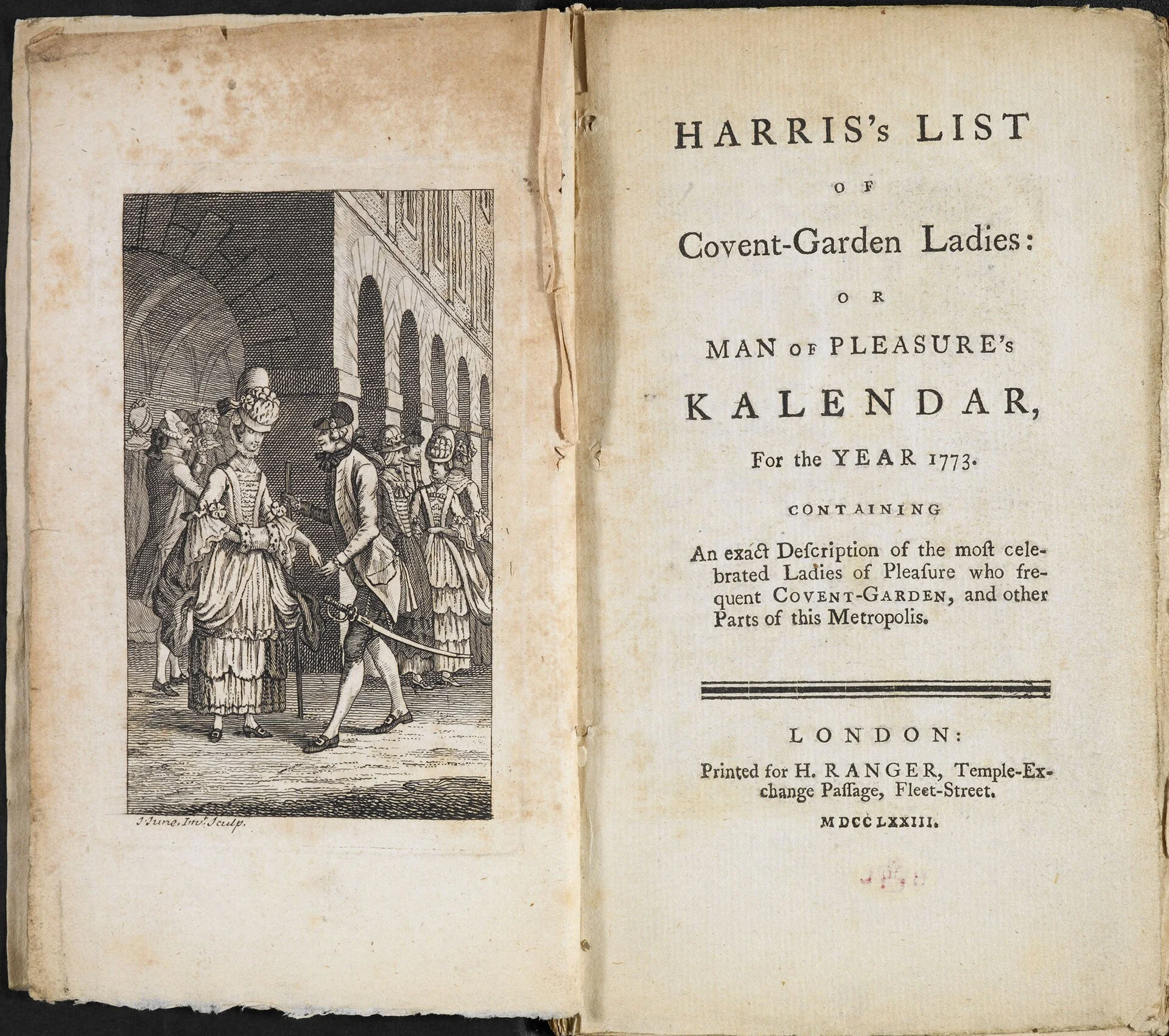

In contrast to the blue plaques, the pink plaques do not highlight celebrities gone by, or even feature famous names. Instead, they champion and make visible women featured in Harris’s List of Covent Garden Ladies, an annual, curated selection of Georgian London’s prostitutes and courtesans that ran from around 1757 to 1795.

The entries for each woman, containing a name, address, short characterising description, and a price, were intended to serve simultaneously as an advertisement for their services, pornography, and local gossip for a presumably middle to upper class Georgian reader. Thus, the only reliable information we can take from the thousands of entries across the less than twenty surviving and accessible copies are a general idea of her physical appearance and manner and her address. Given the nature of the profession, even the name is not fully guaranteed, nor indeed any of the other personal information provided.

Instead of allowing these women to continue to be voyeuristically examined, enjoyed, or objectified by those that came after them, these plaques intend to champion their existence, survival, and visibility in a new way that asks the observer to chiefly consider their humanity and their dignity. Using the only reliable information we have, their address, along with the name they chose or were given when entered into the List, the Pink Plaque Project contextualises these women as a fundamental aspect of London’s social fabric and history who deserve to be acknowledged with compassion and without judgement. By celebrating them as individuals, this project challenges the viewer to consider their profession as merely an aspect of their life instead of a sentence or a definition and questions the narrow ways we may think about women or people of the past.

The Pink Plaque Project also encourages critical reflection on its inspiration, the blue plaques, which overwhelmingly celebrate male and white figures and are not representative of London’s historical or current diverse cultural fabric. Although the project was set up in 1866, as of 2024, over 85% of London’s blue plaques commemorate men. The disparity is so great that at the current rate, it would take 300 years to reach equality – and it would still take 50 years if only women were given plaques from now on. Despite English Heritage launching the ‘plaques for women’ campaign in 2016 to try to address the imbalance, only a third of the over 100 plaque nominations by the public between 2016 and 2018 were female.

The situation is even more dire when it comes to racial diversity, with over 96% of London’s blue plaques commemorating white people in 2021. The first plaque to celebrate a non-white historical figure was Mahatma Gandhi’s in 1954, and the first plaque commemorating a black individual, the composer Samuel Coleridge-Taylor, was only put up over 20 years later in 1975.

Despite recent efforts by English Heritage to address these gender and racial disparities, the fact remains that the people given commemoration and visibility as important aspects of London’s history are hugely overrepresented by one group, and as such it actively encourages those seeing and engaging with the plaques to imagine the city’s history as being primarily or even exclusively shaped, changed, occupied, and steered by white and male individuals.

The Pink Plaque Project serves as a reminder that this was not the case.

If you see a pink plaque while you are walking in a part of London where you live, work, or simply visit, take a moment to think about who these women were as individuals and not just sex workers, imagine what the area may have looked like when they lived here and the different kinds of people they may have seen or known, and remember to recognise and have compassion for the people working and living in London today who may have been forced or felt they had no other option than to enter into difficult and exploitative professions or situations due to the conditions of their environment.